A proverb is a short, commonly known saying that expresses a general truth, piece of wisdom, or advice based on experience. Proverbs are often metaphorical and passed down through generations, forming part of a culture’s oral tradition.

Proverbs have deep roots in human culture, often emerging from oral traditions and evolving over centuries. Many proverbs originate from folk wisdom, religious texts, and historical events, reflecting universal truths and shared human experiences.

“Close but No Cigar”

The phrase most likely originated in the 1920s when fairs, or carnivals, would hand out cigars as prizes. At that time, the games were targeted towards adults, not kids. Yes, even in the ’20s, most carnival games were impossible to win, which often led the game owner to say, “Close, but no cigar” when the player failed to get enough rings around bottles or was just shy of hitting the target. As fairs started to travel around the United States, the saying spread and became well-known.

“Piqued my Interest”

The word “pique” dates back to the 1500s. If you thought that maybe the word sounded or looked French because of the “QU” pronounced like a “K,” you’d be right! It comes from the Middle French verb piquer, which means “to prick.” So, there’s a direct connection between harm and injury, leading to the word’s modern-day connection with emotional harm. And, as Merriam-Webster points out, the more common, positive definition, as in “piqued my interest,” is still tangentially related to the piquer (“to prick”) word. While it may not be painful, arousing your interest or curiosity is still an abrupt emotional response to a stimulus.

“Break a Leg”

The phrase is believed to be rooted in the theatre community, which is known to be a bit superstitious. Performers believed saying “good luck” would bring bad luck on stage, so they’d tell one another to “break a leg” instead. That way, the opposite would happen. Instead of breaking a leg, the performer would put on a flawless performance. It’s believed to have originated in the American theatre scene in the early 20th century. Some believe it was adapted from the German saying “Hals-und Beinbruch,” which means “neck and leg break.” That phrase may also be derived from the Hebrew blessing “hatzlakha u-brakha,” which means “success and blessing.”

“Kill Two Birds with One Stone”

If you say that doing something will kill two birds with one stone, you mean that it will enable you to achieve two things that you want to achieve, rather than just one.

In its present form, the earliest printed record of the idiom was found in 1656.

Prior to that, some believe it originated from the story of Daedalus and Icarus. This doesn’t mean the words can be found verbatim in the story, but that the story itself (or plot points within it) might be the first most concrete use of the metaphor for accomplishing two things with one action. 1 – Daedalus kills two birds with one stone to get the feathers of the birds and make the wings. 2 – Father and son escape from the Labyrinth by making wings and flying out. Two birds. One action. Twice.

“Bite the Bullet”

The idiom “bite the bullet” likely originates from battlefield surgeries where patients were given a bullet to bite down on during painful procedures without anesthesia. This practice was a way to distract them from the pain and keep them from clenching their jaws too tightly, potentially breaking their teeth. The soft lead bullets were readily available and malleable, making them suitable for this purpose.

“What does the o in o’clock stand for?”

Though some folks think that the o in o’clock stands for “on the,” it actually comes from the phrase of the clock. When we use the word o’clock, we’re saying that it’s a particular hour “according to the clock.” For example, “it’s almost 4 o’clock” means the same thing as “it is almost 4 according to the clock.”

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the phrase of the clock can trace its origin back to 1384. This coincides with the growing popularity of mechanical clocks in Europe, the first of which were thought to have been built between 1270 and 1300 in northern Italy and southern Germany. Before this, time was often measured by sundials or shadow clocks. As clocks became more prevalent, of the clock became a standard way to indicate time.

“An apple a day keeps the doctor away.”

The saying “an apple a day keeps the doctor away” is a popular 19th-century proverb that encourages eating apples for overall health and well-being, but it’s not scientifically supported. While apples do offer some health benefits, there’s no evidence that eating them regularly significantly reduces the need for doctor visits.

“SOS”

The term SOS is a Morse code sequence, deliberately introduced by the German government in a 1905 set of radio regulations to stand out from less important telegraph transmissions. Unlike acronyms, where each letter represents a specific word, SOS doesn’t stand for anything. Still, because the term is so prevalent in marine contexts, people often confuse it for an abbreviation or acronym for phrases like “save our souls” and “save our ship.” Three dots, three dashes, three dots. At a time when international ships increasingly filled the seas and Morse code was the only way to communicate instantaneously between them, vessels needed a quick and unmistakable way to signal that trouble was afoot. SOS is a palindrome (a word that reads the same backward and forward) and an ambigram (a word that looks identical whether read upside down or right side up).

“Strike while the iron is hot.“

The idiom “strike while the iron is hot” originates from the practice of blacksmithing. It refers to the need for a blacksmith to shape iron quickly when it’s red hot and malleable, before it cools and becomes difficult to work with. This metaphor translates to seizing opportunities and acting decisively before they pass.

“Curiosity killed the cat.“

“Curiosity killed the cat” is a proverb used to warn of the dangers of unnecessary investigation or experimentation. The original form of the proverb, now rarely used, was “care killed the cat”. The modern version dates from at least the 19th century.

The origin of “curiosity killed the cat” is debated, but the phrase’s earliest known usage in a play by Ben Jonson in 1598 was “care will kill a cat”. Shakespeare later used this in his play, “Much Ado About Nothing”. Over time, “care” evolved to “curiosity,” with the modern form appearing in a compendium of proverbs in 1873.

“I can’t put my finger on it.“

The idiom “I can’t put my finger on it” means that you sense something is wrong or have a feeling about something, but you can’t pinpoint the exact reason or detail. It’s like trying to understand something, but you’re not quite grasping it.

The idiom came into use in the late 1800s. The expression alludes to the image of someone looking through a document or book and literally placing a finger on the words that will support their assertion. Often, the phrase is used in the negative, as in “I can’t put my finger on it,” to mean you cannot identify the cause of something, remember something, or understand something.

“Pass the Time“

The phrase “pass the time” refers to using an interval of time in a productive or engaging way, such as reading a book or playing a game while waiting. The origin of “pass the time” is linked to the French word passe-temps, which means “recreation, diversion, amusement, sport”. The English phrase “pass the time” emerged around the same time as the French term, suggesting a shared origin.

The phrase “pass the time” derives from the French passe-temps, which was used in the late 15th century. The English word “pastime” also emerged in the Middle English period, around 1473, and is formed by compounding the words “pass” and “time”.

“Pipe Dream”

A “pipe dream” is an idiom that refers to a hope or plan that is unlikely or impossible to achieve; it’s a fantasy or a wish that’s not realistic.

The term likely originated from the notion of opium pipes, which could lead to dreamlike states, implying that the thoughts and visions experienced while using such pipes were fanciful and unrealistic.

Essentially, calling something a “pipe dream” means expressing that it’s a highly improbable or unattainable goal or idea.

“Mind Your Own Beeswax”

The phrase “mind your own beeswax” likely originated as a more informal and playful way of saying “mind your own business,” possibly emerging in the 19th or early 20th century.

One theory suggests that it arose from the practice of women using beeswax to cover blemishes or skin imperfections, so being told to “mind your own beeswax” meant “don’t stare at my skin.” Another theory links it to the colonial practice of making candles, where a distracted person might be reminded to focus on their own work.

“Out of the Blue”

Blue refers to the clear blue sky. Typically, a thunderstorm does not happen when the sky is clear blue. When it happens, that surprises us since it is unexpected. This explains the ‘connection’ to “blue” in the idiom.

According to some English scholars, the idiom is a derivation of an old idiom “a bolt out of the blue” or “a bolt from the blue,” which refers to a completely unexpected and surprising act, like a thunderbolt from a clear blue sky.

“How Art Thou”

“How art thou” is an archaic English phrase meaning “how are you?”. “Art” is an old form of “are,” and “thou” is an old form of “you”. This phrasing is commonly found in older literature, like Shakespearean plays, but is not used in modern English.

“Piece of Cake”

This expression originated in the Royal Air Force in the late 1930s to describe an easy mission, and the precise reference is as mysterious as that of the simile ‘easy as pie’. Possibly, it evokes the easy accomplishment of swallowing a slice of sweet dessert.

“Stuck in my Craw”

The idiom “stuck in my craw” originates from the anatomical feature of a bird’s craw, a pouch in the esophagus that stores food before it’s ground by the gizzard. The phrase is a metaphor for something that cannot be accepted, tolerated, or easily let go, much like a bird struggling with an unswallowable object stuck in its craw.

“Dollar = Buck”

The most widely accepted theory points to buckskin—specifically, the skins of male deer. In the early days of North American colonization, when settlers traded goods with the Native Americans, animal pelts were used as a form of currency. “Buckskins were commonly used as an element of barter, even as far back as the 1740s”.

Early records from traders and pioneers during the 18th century frequently mention prices being listed in bucks. “They were kind of stacked like paper money, and you would trade a buck for this and a buck for that, and a buck would be one deer skin”. So when someone said something cost a buck, they literally meant it cost one pelt. The slang term carried over seamlessly into the emerging cash-based economy, and buck evolved into an actual dollar.

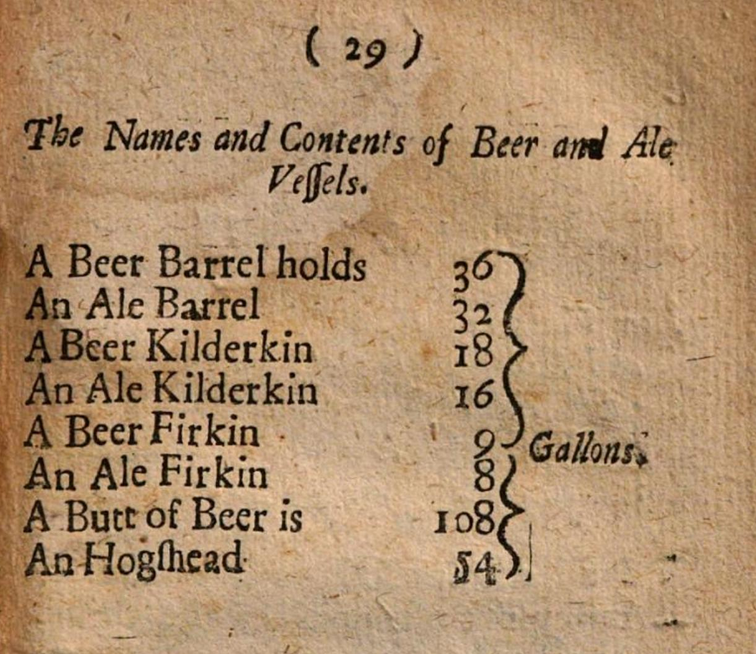

“Buttload”

The phrase “buttload” originates from the medieval term “butt,” which was a standard unit of measurement for large casks of wine or ale. One butt, or buttload, contained approximately 126 gallons (or about 477 liters) and was used in England and Europe for commercial trade and transportation of liquids. The term has since evolved into colloquial slang for any large quantity of something.

“Pardon my French“

In 19th-century Britain, English speakers used the phrase pardon my French literally when slipping French words into conversation. Because not everyone spoke French, people would politely excuse themselves with pardon my French.

Over time, the meaning of pardon my French shifted to cover profanity or strong opinions because “the word French is the real target in the phrase. French just became an English word for anything risqué.

“Barn Burner“

The idiom “barn burner” originated from the mid-19th-century radical political faction known as the Barnburners, who were said to be willing to “burn down the barn to get rid of the rats”. The term evolved to describe any exciting, impressive, or tumultuous event, like a heated political debate or a close sports game.

“Saved by the Bell“

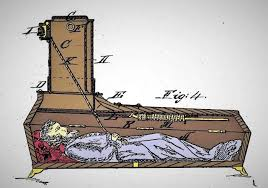

“Saved by the bell” originates from the 18th century, when people were so fearful of being buried alive that they would be buried with a string attached to a bell on the surface. If, after being buried, the “deceased” came around, they could ring the bell to alert people.

“Graveyard Shift“

The term “graveyard shift” originates from the 18th century, when people were so fearful of being buried alive that they would be buried with a string attached to a bell on the surface. After a burial, a person would be nominated to do the “graveyard shift” (literally sit in the graveyard) to check that the buried person didn’t wake up and start ringing the bell.

It may also stem from 19th-century watchmen who guarded graves to deter body snatchers seeking corpses for medical schools.

“Deadline“

The word seems to have emerged during the American Civil War from the Confederate Andersonville military prison, where it was used to designate a line, either actually drawn or simply understood, beyond which if prisoners stepped, they would be shot to death.

“Skeleton in the Closet“

The expression originated in the medical profession (or in British English, Skeleton in the Cupboard). Doctors in Britain were not permitted to work on dead bodies until an Act of Parliament enabling them to do so was passed in 1832. Before this date, the only bodies they could dissect for medical purposes were those of executed criminals. Although the execution of criminals was far from rare in 18th-century Britain, it was doubtful that a doctor would come across many corpses during his working life. It was therefore common practice for a doctor who had the good fortune to dissect the corpse of an executed criminal to keep the skeleton for research purposes. Public opinion would not permit doctors to keep skeletons on open view in their surgeries, so they had to hide them. Even if they couldn’t actually see them, most people suspected that doctors kept skeletons somewhere, and the most logical place was the cupboard. The expression has now moved on from its literal sense!

“Spill the Beans“

One possible explanation for the origin of the phrase “spill the beans” dates back to ancient Greece, where people would use beans to vote: white beans for positive votes and dark beans for negative votes. These votes were cast in secret, so if someone knocked over the beans in the jar—whether by accident or intentionally—they would spill the beans and reveal the results prematurely.

“Cost an Arm and a Leg“

Back in the 18th and 19th centuries, having your portrait painted was a luxury, and artists charged based on how much of your body was included in the painting.

A simple head-and-shoulders portrait was the basic package, but if you wanted your arms and legs painted too, the price went way up. So literally, including arms and legs in your portrait costs extra arms and legs!

“The Whole Nine Yards“

One popular theory about this idiom involves World War II fighter pilots, whose ammunition belts were exactly nine yards long. When a pilot used up all their ammo in a fight, they had given it “the whole nine yards.” Bombs away!

“Kick the Bucket“

The phrase “kick the bucket” means to die and has been used since the 18th century. One theory connects it to the Catholic tradition of placing a bucket of holy water by the feet of the deceased for mourners to sprinkle.

Another theory suggests the term comes from 16th-century England, where “bucket” referred to a beam. When animals were hanged for slaughter, they would kick the beam as they died, giving rise to the idiom.